by Pooja Bhatia. Originally posted at ozy.com

To know Mario Joseph is to wait for Mario Joseph. You will wait for him to return from a last-minute hearing, to stop barking into one of his two mobile phones, to wrap up a meeting that started an hour late. And you will wait because Joseph, managing attorney at the NGO Bureau des Avocats Internationaux, is the best human rights lawyer in Haiti, a country where human rights are honored mostly in the breach. From dawn till dusk, clients gather on his office’s bougainvillea-laced terrace: brave women going after rapists, homeless Haitians evicted from post-quake tent camps, cholera victims seeking reparations.

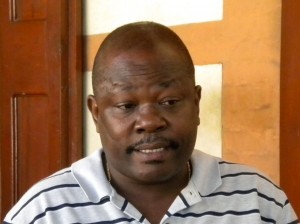

Joseph’s eyes are often red-rimmed from lack of sleep, but his suits are sharp, his ties are sumptuous and his shoes and fingernails are buffed till they shine. With his percussive Creole and typically stern countenance, Joseph can be intimidating. It’s easy to forget that he was raised in rural poverty by a single mother who couldn’t read, and that he managed to get a law degree only through a series of flukes and his own determination. If fate had had its way, Joseph would have been like the millions of Haitians who never attend school, never see a doctor and live on less than $2 per day.

Instead, he’s fighting two of Haiti’s most compelling human rights battles and the behemoths behind them.

The first is against Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, the dictator who fled Haiti in 1986 only to make a surprise return in 2011. Duvalier stands accused of mass political violence — an estimated 3,000 people died in the torture chambers known as Fort Dimanche, and countless others disappeared or were forced into exile — and groups from Human Rights Watch to Amnesty International demanded that he be held accountable. But under a Haitian government said to be sympathetic to the former tyrant, the wheels of justice seemed to grind to a halt. Last year, a trial court threw out the case, saying that Haiti doesn’t recognize crimes against humanity. Baby Doc let loose in restaurants and nightclubs and was photographed shaking hands with the then-U.N. Special Envoy to Haiti Bill Clinton.

Many Haitians were resigned: Impunity is the norm in their country; justice, the exception. But Joseph set out to change that, and in February, the 61-year-old Duvalier was summoned to an appeals court to face his accusers for the first time in history. A judge’s ruling on whether Duvalier can be tried has been delayed, but for Joseph and his clients, the Duvalier prosecution shows that justice is possible in Haiti. It’s a novel notion and “a huge step,” Joseph said. “It means that if you’re persistent, if you fight, if you organize, if you push the system, it can move. It gives you hope. You can see it on my clients’ faces.”

”When he is representing his clients, Mario has no fear,” says Amanda Klasing, a researcher with Human Rights Watch who has been following the case and who has known Joseph for six years. “He puts people who typically don’t have access to justice on an equal playing field with some of the most powerful forces in Haiti, and in a really magnificent way. I like to see him at work.”

The second behemoth is the United Nations. Yes, the world’s premiere advocate for human rights stands accused of a major violation: importing cholera into Haiti through grossly inadequate sanitation at a U.N. peacekeeping base. (Think broken pipes and waste pits emitting infected sewage into the tributary of a major river.) The water-borne illness, not documented in Haiti until October 2010, has since killed 8,200 people and infected 7 percent of the population. The great weight of scientific evidence pinpoints the U.N. — even a July report by a U.N.-appointed expert panel.

Joseph and his partners filed claims on behalf of 5,000 cholera-affected Haitians seeking damages, an apology and long-term investment in sanitation infrastructure. The U.N. has insisted that its immunity protects it against the claims, which it calls “not receivable.” Joseph’s next step: filing in U.S. and Haitian courts. If the case is heard, it could have worldwide implications for peacekeeping operations and aid accountability.

It’s a controversial suit, and critics fear that it might impede peacekeeping operations around the world. But for Joseph, as for most Haitians and many in the international human rights community, the right thing to do is clear. “It’s a veritable debacle for the U.N.,” he says. ”There’s a huge contradiction between the values they promote and their behavior in countries like Haiti. Imagine if this had happened in the U.S. or France or Canada…” Joseph trailed off. “Well, it wouldn’t happen there.”

Joseph’s pugnacity has gotten him in plenty of trouble back home. Just in the past year, he’s been on the receiving end of intimidating phone calls, cars tailing him, and police officers rifling through his office. And it’s been a pretty normal year on the threats-and-intimidation barometer.

“The term ‘hero’ gets thrown around way too easily, but I’m not sure there’s a better term for someone who absolutely risks his life every day when he goes to work — and does it for very little personal, tangible reward,” says Fran Quigley, a professor at Indiana University’s law school.

So what keeps him going? Joseph name-checks his supporters abroad, yet it’s clear that compassion, duty and a love for battle stoke the fires. “It’s my responsibility to participate in the construction of democracy here,” he says. If it sometimes seems a Sisyphean task, Joseph knows one thing above all: “Justice is never going to come unless you fight for it.”

Under Creative Commons License: Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives