by Jacqueline Charles and Curtis Morgan, The Miami Herald, Oct. 28, 2012

Haitian Prime Minister Laurent Lamothe peered from the helicopter window and paused, as if needing time to process the ravaged landscape below: washed-out roads, rotting crops, flooded roads and raging rivers flowing with mud. “We have a big job to do,’’ Lamothe said to Sen. Steven Benoit, a member of the opposition party, who was along on a grim damage survey Saturday.

Haitian Prime Minister Laurent Lamothe peered from the helicopter window and paused, as if needing time to process the ravaged landscape below: washed-out roads, rotting crops, flooded roads and raging rivers flowing with mud. “We have a big job to do,’’ Lamothe said to Sen. Steven Benoit, a member of the opposition party, who was along on a grim damage survey Saturday.

With the death toll rising to at least 51 and an estimated 200,000 homeless as a result of four days of relentless rain from Hurricane Sandy, Lamothe appealed for patience and called for investment in flood-control structures that are largely absent from the countryside. But he also expressed a weary frustration, one shared by many in this poor nation reeling from a string of natural disasters. With each one, he said, Haiti has taken a step backward. “It should not be normal that every time it rains, we have a catastrophe throughout the country,” Lamothe said.

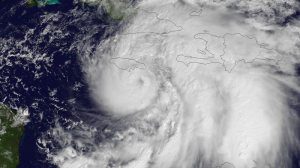

As Haiti began what will be grueling months of cleanup from a powerful Category 2, 115-mph hurricane that left a trail of destruction and killed at least 64 people in the Caribbean, millions of people in the northeastern United States were bracing for what meteorologists and emergency managers fear could be a disaster of epic proportions…

In Haiti, the United Nations and the Haitian government were trying to put a price on the loss, but it will be an arduous process with many areas isolated by impassable roads. Once again, it had not taken a direct hit from a tropical storm to wreck Haiti — the core of Sandy, like Isaac earlier this year, had skirted the country.

The Office of Civil Protection raised the total of known dead in Haiti on Saturday to 51, with at least 15 missing and 18 injured. More than 21,107 were in shelters and an estimated 200,000 were homeless after the storm in a country where more than 350,000 are still homeless after a devastating earthquake in 2010.

Along Haiti’s hard-hit southern coast, no community seemed to have been spared. From the air, coconut trees looked like wet mops, large farms stood in pools of water and eroded soil from the denuded hillsides turned the sea the color of mocha.

Haitians were caught off guard by what some are calling “the Caribbean storm” because it came from the sea to the south, not out of the Atlantic Ocean. The storm, say Haitian and international aid officials, dumped more rain than Tropical Storm Isaac in August and Tomas in 2010 after the earthquake.

In the city of Les Cayes, among the hardest-hit areas, the storm dumped a stunning 27 inches of rain in a 24-hour period, said Johan Peleman, director of the United Nations humanitarian agency in Haiti.

In areas the government and aid agencies could reach, thousands of hot meals were to be distributed, Lamothe said. “Given the situation we are living today, it will not be easy,” he said. “We need the patience of everyone. We will not be able to get to everyone at the same time.”

Lamothe said the government plans to launch a country-wide retaining wall project to protect villages built along rivers criss-crossing the mountainous nation. In some communities like Leogane, rivers were still rising from flood water spilling down from the hills. “People cannot think that everything is over. Things are not over yet,” said Benoit, who invited himself on the helicopter tour. “This is a national problem.”

This story was supplemented by information from The Associated Press.