by Frances Robles. Originally posted at The New York Times

Thirty years to the day after Haiti’s last dictator fled the impoverished nation as it took its first wobbly steps toward democracy, another leader stepped down Sunday, without a successor to take his place.

Thirty years to the day after Haiti’s last dictator fled the impoverished nation as it took its first wobbly steps toward democracy, another leader stepped down Sunday, without a successor to take his place.

The president, Michel Martelly, left office amid an electoral crisis that underscored how Haiti has struggled to maintain democratic order since the 1986 ouster of Jean-Claude Duvalier.

Mr. Martelly departed at the end of his five-year term, thanks to a last-minute agreement that laid out steps to choose a provisional government to take his place. Although the agreement left major doubts about who will govern the nation in the months to come, experts hailed it as an important move toward at least temporarily resolving a political impasse that had put hundreds of protesters on the streets.

At least one person was beaten to death Friday, as former army soldiers supporting Mr. Martelly hit the streets to counter protests that demanded his ouster.

“I said I would not hand over power to those that don’t believe in elections, but the Parliament guaranteed that they will do everything to make sure the process carries on,” Mr. Martelly said in his last speech to Parliament, before handing the presidential sash to the leader of the National Assembly. “I am leaving office to contribute to constitutional normalcy.”

Mr. Martelly, a former pop music star, was criticized for failing to hold elections during his five years in office and for surrounding himself with cronies, some of them criminals. He never shed his garish style and was considered an autocrat who let Parliament expire during his tenure.

But Mr. Martelly said he had “faced the impossible” when he “inherited pain and misery” five years ago, a year after a huge earthquake killed hundreds of thousands of people and toppled sections of the capital.

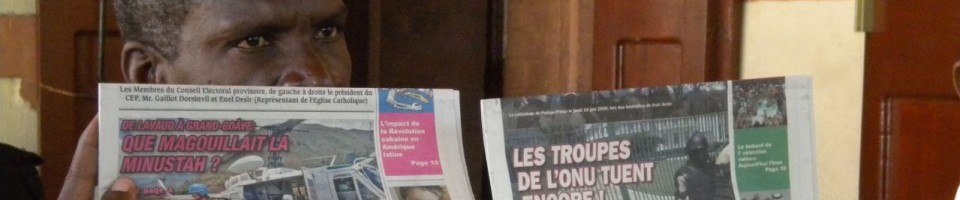

Haiti’s latest political crisis resulted from a presidential election held in October with 54 candidates and that critics said was riddled with fraud. Political operatives were able to vote multiple times, and the president’s handpicked successor came in first despite being a virtual unknown, leaving the 52 candidates who did not make the runoff vote to question the results.

The runoff was delayed twice as protesters demanded clarity.

Mr. Martelly insisted that there had been no fraud and that the runoff should take place, urging voters to choose his candidate, Jovenel Moïse, a banana exporter. But a former government official who officially came in second, Jude Célestin, refused to participate in the runoff until a new electoral council was chosen and a thorough review of the first round was conducted.

Under the accord reached this weekend, the prime minister will stay until an interim president is chosen by both chambers of Parliament. Once the interim president is in place, a consensus prime minister will be chosen, and a verification commission will review the October balloting.

“The headline should read: ‘A blood bath was avoided,’ ” said an official at the Organization of American States, which sent a special delegation to Haiti to help resolve the crisis. He spoke on the condition of anonymity because of the diplomatic delicacy of the matter.

The official said 28 meetings had been held to reach an agreement, many into the early hours of the morning. Mr. Martelly agreed to allow a member of an opposition party to be selected as interim president, an important concession.

The agreement stipulates that an election will be held by April 24, and a new president installed May 14. John Kirby, a State Department spokesman, said the agreement was a step toward ensuring “the continuity of governance and the completion of the ongoing electoral process.”

Robert Fatton Jr., a political scientist at the University of Virginia who follows Haiti closely, said, “It’s all nice and jolly, but there are real problems.”

He said disputes could arise if the commission verifying the last election determined that different candidates should proceed to the runoff, or if the election results should be scrapped altogether.

“The old military people that are out on the streets are sending a clear signal to opposition groups: ‘If you don’t accept this compromise, we are out here, with weapons,’ ” Mr. Fatton said. “No one knows who was in charge of these people. Everyone assumes they are in fact armed people and armed by the Michel Martelly regime, otherwise they would not be so free to go to the streets.”