by Judith Scherr. Originally published by Countercurrents.org

Haiti’s brutal army was disbanded in 1995, yet armed and uniformed paramilitaries, with no government affiliation, occupy former army bases today.

Haiti’s brutal army was disbanded in 1995, yet armed and uniformed paramilitaries, with no government affiliation, occupy former army bases today.

President Michel Martelly, who has promised to restore the army, has not called on police or U.N. troops to dislodge these ad-hoc soldiers.

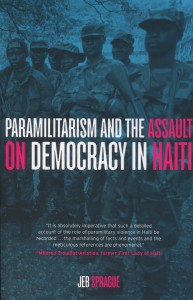

Given the army’s history of violent opposition to democracy, Martelly’s plan to renew the army “can only lead to more suffering”, says Jeb Sprague in his forthcoming book Paramilitarism and the Assault on Democracy in Haiti, to be released mid August by Monthly Review Press.

The role of Haiti’s military and paramilitary forces has received too little academic and media attention, says Sprague, a doctoral candidate in sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He hopes his book will help to fill that gap.

Sprague researched the book over more than six years, traveling numerous times to Haiti, procuring some 11,000 U.S. State Department documents through the Freedom of Information Act, interviewing more than 50 people, reading the Wikileaks’ files on Haiti, and studying secondary sources.

The author is an academic, but he doesn’t strive for neutrality. His is an unapologetic belief in the right of the Haitian masses to control their destiny.

To support his narrative, Sprague includes 100 pages of footnotes.

“I know there will be critics of the book,” he told IPS, “I wanted to have a lot of information there to back up what I’m saying, so it’s not just seen as conjecture or rumour.”

In his historical analysis, Sprague takes the reader back to the “poison gift” the U.S. gave Haiti during its 1915-1934 occupation: an army “that would continue the U.S. occupation long after U.S. troops were gone,” Sprague writes, explaining that U.S. Marines created an army “subservient to the interests of the U.S., the bourgeoisie, and the big landowners”.

Sprague writes about the period of the father and son dictators Duvalier, 1957-1986, when the U.S. considered the Haitian army a “bulwark” against the spread of communism. He explores the military’s “incestuous” relationship to the Duvaliers’ infamous Tontons Macoute, whose purpose, he writes, was “to extort and attack government critics, often acting as secret police or executioners”.

After the Duvaliers, paramilitary forces continued their violence. In 1988, gunmen were thwarted in their attempt to murder the liberation theologian priest Jean Bertrand Aristide, whose popularity was rising; 13 people were killed and 80 injured in the attack.

The gunmen didn’t act alone. Sprague ties these paramilitaries to a former Macoute trained at the School of the Americas, the mayor of Port-au-Prince and wealthy businesspeople.

Throughout the book, Sprague underscores links between paramilitary forces committing overt violent acts and the often-hidden forces of wealth, and national and international political power supporting the paramilitaries.

In 1991, Aristide became the first democratically elected president of Haiti, but the army overthrew him after less than eight months in office. The military didn’t act alone. Sprague writes that it took Haitian elites, officials in Santo Domingo, Washington and Paris, and “even the Vatican” to pull off the coup.

In 1994, President Bill Clinton and 20,000 Marines returned Aristide to office. Aristide presided over a government that was weakened by the terms of his reinstatement, particularly an agreement to drastically reduce tariffs on rice, a severe blow to Haiti’s rural economy.

Aristide disbanded the army in 1995, an act celebrated by the masses, but one that former and would-be military personnel continue to revile today.

Disbanding the army did not rid the country of militarism. Few soldiers surrendered their guns; many fled to the Dominican Republic.

Still others were integrated into the police force. The U.S. took advantage of the situation, bringing recruits to the state of Missouri for training. Sprague quotes Aristide’s legal counsel Ira Kurzban, who visited Ft. Leonard Wood in Missouri.

“’When we drove into the base … the first thing we saw was an army intelligence unit,’” Kurzban writes in an email to Sprague. “’We later learned that the infiltration process began at Ft. Leonard Wood and the U.S. intelligence concept was to pick those people (or push those people) who they thought would be leaders in the police, corrupt them, and have them at the U.S. government’s disposal.’”

“’When we drove into the base … the first thing we saw was an army intelligence unit,’” Kurzban writes in an email to Sprague. “’We later learned that the infiltration process began at Ft. Leonard Wood and the U.S. intelligence concept was to pick those people (or push those people) who they thought would be leaders in the police, corrupt them, and have them at the U.S. government’s disposal.’”

A unique contribution of the book is Sprague’s detailed analysis of the role of neighbouring Dominican Republic in support of Haitian paramilitaries.

In 2000, just before Aristide was to take over from President Rene Préval for his second term, paramilitaries attempted a coup which failed. Those responsible fled to the D.R. Haiti asked for their return, but D.R. officials refused.

Over the next few years, the D.R. would provide a safe haven for paramilitary forces making murderous incursions into Haiti and returning to safety in the D.R.

Neither the U.S. nor the Organisation of American States “put pressure on the Dominican government to stop…the cross-border murder sprees,” Sprague told IPS.

During this period, the U.S. funded opposition parties that Sprague says met in the D.R. with paramilitaries.

Skewed media reporting also supported the paramilitaries and their allies. Opposition protests usually drew a few hundred people and could depend on media coverage. But, Sprague wrote, Aristide’s Lavalas movement “could count on huge rallies…but it had the coverage of only a few small grassroots and government-financed media outlets….”

While paramilitaries dramatically destroyed police stations to take control of a number of cities and towns, it was U.S. officials in the dead of night that physically removed Aristide, quietly flying him to a seven-year exile.

With Aristide gone, the paramilitaries took on new roles. “In March 2004,” Sprague writes, “a reinvigorated paramilitary campaign was launched in the face of an anti-coup backlash by Haiti’s poor, who organized huge demonstrations and rallies.”

On the civilian front, the U.S., France and Canada set up an interim government headed by a Haitian-born Floridian. Sprague writes: “At the top of their agenda was stabilizing the country and securing it as a platform through which global capital could flow freely.”

The U.S. stance toward the paramilitaries was inconsistent. Sprague writes that soon after the coup, the U.S. ambassador spoke on Haitian radio in their favour, but later recognised that the ex-military might eventually undermine the government.

Some 400 paramilitaries were integrated into the police force after the 2004 coup. Haiti’s small police force works, sometimes uneasily, with the 10,000 UN troops stationed in Haiti since the coup.

Today, Sprague writes, “with a large U.N. presence, a new kind of ‘normality’ was forced upon the country. Following the horrendous earthquake of January 2010, and with the return of Jean-Claude Duvalier and the controversial election of Michel Martelly… disgruntled ex-army paramilitaries have gained more freedom. Numerous neo-Duvalierists and rightist ex-army work key security positions for the Martelly government….”

“And Martelly’s trying to bring back the army; but he’s saying, ‘Oh it’s not a military.’ They have a different name they’re giving it (the ‘public security force’),” Sprague told IPS, adding that today, as in the past, “the elites are trying to find the right ingredient to maintain their control.”

Jeb Sprague will be traveling around the U.S. and Canada with his book. For information, see http://jebsprague.blogspot.com. He’ll be in Toronto on September 19th.

Jeb Sprague will be traveling around the U.S. and Canada with his book. For information, see http://jebsprague.blogspot.com. He’ll be in Toronto on September 19th.