Originally posted at Al Jazeera English.

Officials fear rising food prices and an increase in cholera cases in Caribbean nation where storm killed 52 people.

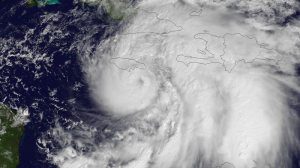

As Sandy causes havoc throughout the eastern US, the full extent of the storm’s damage is just beginning to emerge in the Caribbean nation of Haiti.

As Sandy causes havoc throughout the eastern US, the full extent of the storm’s damage is just beginning to emerge in the Caribbean nation of Haiti.

The UN is warning that flooding and unsanitary conditions could lead to a sharp increase in cases of cholera, while aid workers are worried that extensive crop damage will mean that food prices will rise.

Extensive damage to crops throughout the southern third of the country, as well as the high potential for a surge in cases of cholera and other water-borne diseases, could mean Haiti will see the deadliest effects of Sandy in the coming days and weeks.

Haiti has reported the highest death from Sandy so far, as swollen rivers and landslides claimed at least 52 lives, according to the country’s civil protection office.

More than three days of constant rain left roads and bridges heavily damaged, cutting off access to several towns and a key border crossing with the Dominican Republic.

“The economy took a huge hit,” Laurent Lamothe, prime minister, told Reuters news agency.

He also said Sandy’s impact was devastating, “even by international standards”, adding that Haiti was planning an appeal for emergency aid.

“Most of the agricultural crops that were left from Hurricane Isaac [in August] were destroyed during Sandy,” he said, “so food security will be an issue.”

Coffee crop destroyed

Sandy also destroyed banana crops in eastern Jamaica as well as delete the coffee crop in eastern Cuba.

The widespread loss of crops and supplies in the south, both for commercial growers and subsistence farmers, is what the Haitian authorities and aid organisations had worried about most.

The past several months have seen a series of nationwide protests and general strikes over the rising cost of living. Even before Sandy hit, residents complained that food prices were too high.

A rise in food prices in Haiti triggered violent demonstrations and political instability in April 2008. Jean Debalio Jean-Jacques, the agriculture ministry’s director for the southern department, said he worried that the massive crop loss “could aggravate the situation”.

“The storm took everything away,” Jean-Jacques said. “Everything the peasants had in reserve – corn, tubers – all of it was devastated. Some people had already prepared their fields for winter crops and those were devastated.”

In Abricots on Haiti’s southwestern tip, the community was still recovering from the effects of 2010’s Hurricane Tomas and a recent dry spell when Sandy hit.

“We’ll have famine in the coming days,” Kechner Toussaint, the Abricots mayor, said. “It’s an agricultural disaster.”

The main staples of the local diet, bananas and breadfruit, were ripped out by winds and ruined by heavy rains.

In the southwestern Grand Anse department, a boat that regularly comes from the capital Port-au-Prince to deliver supplies and pick up produce to sell in the capital had not come in more than a week because of the storm. The cost of basic things, such as fuel, had already jumped.

‘Incalculable’ damage

In Camp-Perrin, a mountainous region in the southwest peninsula where Sandy’s first fatality was recorded after a woman tried to cross a swollen river, coffee planters lamented the loss of a harvest they were weeks away from collecting.

“Coffee is the bank account of the peasants,” said Maurice Jean-Louis, a planter and head of a coffee growers’ co-operative in Camp-Perrin.

Rain flooded many storage areas as well, soaking coffee beans that were set aside for export. He called the damage “incalculable.”

In Port-au-Prince, Sandy destroyed concrete homes and tent camps alike, where 370,000 victims of the 2010 earthquake are still living.

Haitian authorities said 18,000 families were left homeless in the disaster.

Aid organisations began reporting a sharp rise in suspected cholera cases in several departments, with at least 86 new cases alone coming from Port-au-Prince’s earthquake survivor camps, according to Juan Carlos Gustavo Alonso of the Pan American Health Organisation.

Many communities are still cut off and only accessible by helicopter, he said, so the broader rise in cholera was “still too early to tell”.

Since October 2010, a cholera outbreak hashit almost 600,000 people and killed more than 7,400 in Haiti.